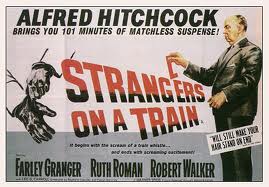

It may have come about as a result of an exhausting train journey I endured a few days ago or possibly because it’s Wimbledon fortnight – tennis being a daily headline at the moment. Maybe it happened because of both of these things or perhaps neither. However yesterday, Hitchcock’s 1951 thriller popped into my mind, vied for my attention and consequently prompted me to put pen to paper, so to speak.

Actually I’m surprised after looking back at the titles I’ve reviewed for this website over the past sixteen months that I’ve only reviewed one other Hitchcock film – North by Northwest. After all, I am a great admirer of his work. Maybe I’ve restrained myself on account of his films having been so extensively written about already but then, when one thinks of his best known films, Strangers on a Train often gets overlooked. And yet for me, it’s one of his finest efforts.

The plot is a simple one and I shall refrain from giving too much away for those who might not yet have seen it. It begins with a chance encounter between two men on a train. Guy Haines (Farley Granger) is a semi-famous tennis player (ergo the Wimbledon connection) with designs on a political career, a slut of a wife, Miriam (Laura Elliott) whom he’s hoping to divorce and a real dish of a girlfriend, Anne Morton (Ruth Roman) who just happens to be the daughter of a senator (Leo G. Carroll). The other man, Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker) is a smooth-talking weirdo with a worrying line in small talk. The two men chat over lunch in Bruno’s compartment and Bruno, who is aware of Guy’s private life via the gossip columns, explains his idea for the perfect murder. A simple criss-cross theory. Two complete strangers with nothing to connect them, swap the murders they would like to commit thereby absolving themselves of any motive and giving the police no clue as to the guilty parties. Bruno says that he’ll murder Guy’s unfaithful wife, leaving him free to marry Anne if Guy will murder Bruno’s overbearing father. Naturally enough, Guy makes a polite but hasty exit from the train compartment however, unfortunately for him, Bruno thinks a deal has been made.

Sometime later, Bruno follows Miriam and her two boyfriends to an amusement park and after a short boat ride, he strangles the life out of her in the darkness on the Isle of Love. Meanwhile Guy is on a train chatting to a drunk college professor who turns out to be an unreliable witness when, called by the police to corroborate Guy’s alibi claim, says he can’t remember their meeting. Guy is shocked and horrified that Bruno actually went ahead and murdered Miriam and is repeatedly harassed by Bruno and told that he now has no choice but to kill Bruno’s father. What ensues is a sublimely constructed thriller, perfectly paced, with just the right amount of humour (supplied in the main by Patricia Hitchcock who plays Anne’s younger sister Barbara) to make it still scary yet hugely entertaining.

Fade outs to black and swipes between scenes are replaced by a quick editing style and often cross-cutting between Guy and Bruno via their dialogue and movements, thereby seamlessly moving from scene to scene, the tempo never letting up. Strangers on a Train is a masterclass in how to build tension all the way to the finale and in true Hitchcock fashion, the climax takes place within a great visual location – this time aboard an out of control carousel spinning like a centrifuge. Implausible it may be with Guy’s legs flailing behind him like a sequence from The Simpsons but the skill behind the execution is evident in its greatness. With fighting and explosions and splintering wooden horses and screaming children it’s an incredible blend of close-ups, miniatures and background projections.

In my humble opinion, the film is worth watching for the Oscar nominated black and white cinematography alone. The gorgeous use of light and shadow is perhaps some of the finest of any Hitchcock film and it would see cinematographer Robert Burks begin a fourteen year run with the director and shooting every one of his remaining pictures with the exception of Psycho in 1960. The lighting is frequently dark and moody and choice camera angles and optical effects – so typical of Hitchcock’s style – add to the overall atmosphere of the film and keep the visuals interesting without ever going too far. There are several almost surreal shots from intriguing angles but perhaps the most famous shot of all (and one that is still studied in academic circles) is when Bruno strangles Miriam at the amusement park, the moment captured in the reflection of her glasses after they fall to the ground during her brief struggle. It’s simply cinematic perfection. Numerous other little blink-and-you’ll-miss-them gems are peppered throughout the film – Guy wiping lipstick off his face before meeting Anne’s father, Bruno’s shadow in the tunnel of love looming over his intended victim, Bruno again standing alone on the Jefferson Memorial, his dark figure an unwelcome stain on the white purity of the structure’s marble. It’s these subtleties, telling us the audience so much, that reveal the genius of the director.

The casting is spot on from the clean-cut figure of Guy Haines to Marion Lorne who plays Bruno’s befuddled mother (another character that adds a little comedy) but the performance of the movie and – one would argue – of his life, comes from Robert Walker. He’s just superb; charming, erudite, a bit of a dandy, but dark, deeply unbalanced, brooding. It was a role meant for him and I couldn’t imagine anyone else doing as good a job as he did. Sadly he died two months after the film’s release aged just 32 but his performance here will live on and be lauded for as long as people watch films.

Of course, all this visual brilliance starts with the written word and this came from a novel of the same name by Patricia Highsmith. In the end there would be numerous differences between novel and screenplay and Hitchcock had a bit of a hard time getting the script he wanted. Originally, he had hopes for a proven writer to lend the project some clout and was looking at people like John Steinbeck and Dashiell Hammett but they showed little interest. Raymond Chandler wrote a draft but fell foul of Hitchcock when the two couldn’t get along and so after a suggestion from Ben Hecht – who had already written Spellbound and Notorious for Hitchcock but was unavailable – he hired Hecht’s assistant Czenzi Ormonde. She was a fair haired beauty who had no formal screen credit but had recently published a collection of short stories which was well received by critics. At their first meeting, Hitchcock encouraged her to forget all about Highsmith’s book and proceeded to tell her the entire story himself. It clearly worked because the film has a crisp linearity from beginning to end and a leanness to every scene. There’s no wasted dialogue and not a single unnecessary frame.

Bottom line – a true classic.