A couple of weeks ago, a well-thumbed copy of Arthur Conan Doyle’s classic 1912 novel The Lost World caught my eye on a bookshelf. Having read and enjoyed at one time or another similar tales of adventure by the likes of Jules Verne and Edgar Rice Burroughs, I took it down and indulged myself. I’ve had great pleasure in reading the majority of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories so therefore I felt certain I was going to enjoy this too. And enjoy it I did. The mix of Victorian characters, exotic adventure and prehistoric fantasy all written with that turn-of-the-century eloquence made it an eminently pleasurable page-turner.

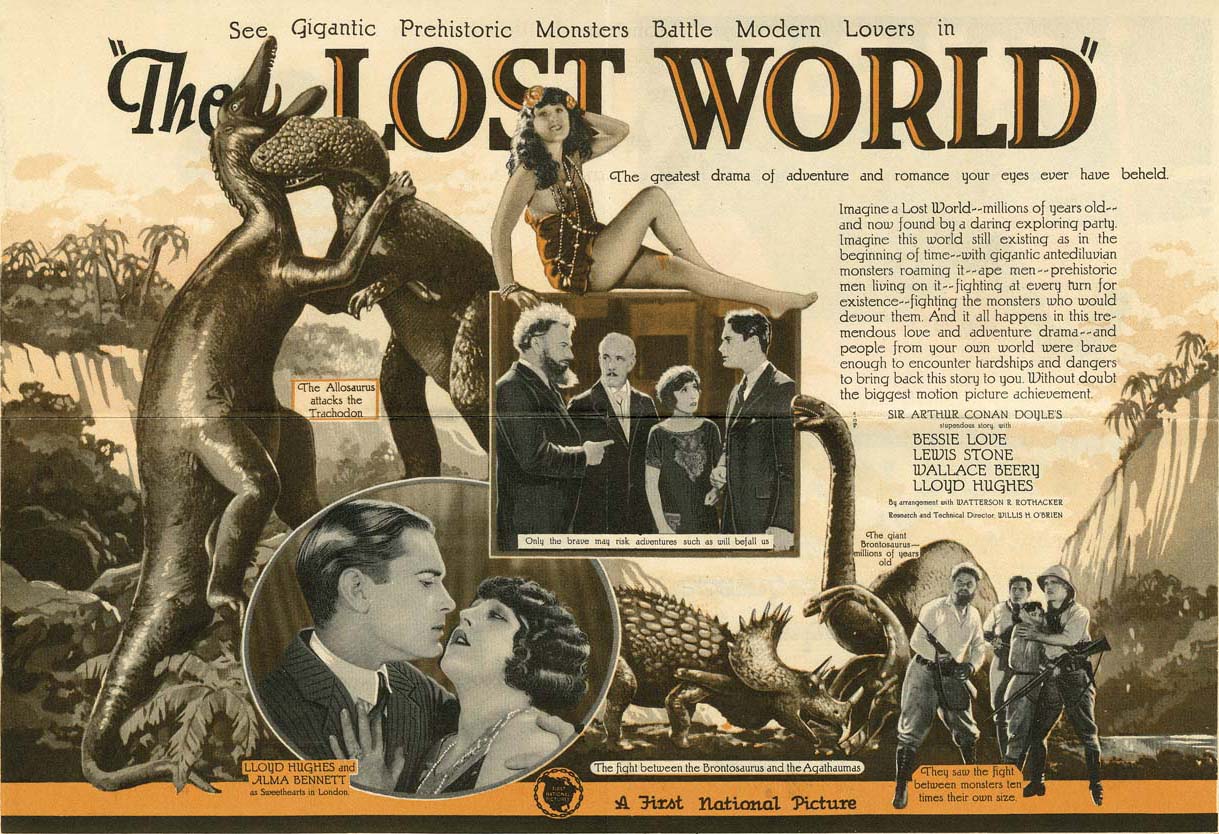

Naturally, upon completion it led me to check out the original filmed version of the story which in turn led me to a comparison with a contemporary one. The first, directed by Harry Hoyt, was made in 1925 and the date of this alone is impressive, not least because this was still the silent era of cinema. One can almost imagine those early studio bosses scratching their heads and wondering how on earth do you take prehistoric beasts off of the page and bring them to life before a paying audience.

The answer was, of course, stop motion special effects and this was the first feature film to use such a technique courtesy of, in this instance, Willis O’Brien. O’Brien was a pioneer of this style of special effects and would become responsible for some of the best-known images in the history of cinema, his best known work perhaps being the greatest monster movie of them all, King Kong (1933). For audiences of the time, it must have been incredible to see dinosaurs moving about on screen when all they had ever seen of them before were drawings on a page. The film itself is significant for this reason and overall it’s worth a viewing not just to see how far cinema has come since those early days but also to see how creative these filmmakers were with the resources they then had.

In the film, Wallace Beery plays the brusque Professor Challenger who leads a group of British explorers into the Amazon in order to prove to the world that a land of prehistoric creatures exists on an isolated plateau. The South American jungle is depicted by set pieces of rainforest and river with the occasional snake dangling from a tree and one or two cutaways to stock footage of a snarling jaguar. The prehistoric plateau is more of the same but with models of distant smoking volcanos and of dinosaurs roaming around or fighting in that uniquely disjointed way that is stop motion animation. One panoramic scene of dozens of dinosaurs fleeing an erupting volcano was created on a tabletop that was 150 ft long by 75 ft wide!

By today’s standards it is, of course, laughably crude but then in this digital age where everything from men made out of liquid metal to flying vampires can be brought to life so convincingly, we’ve all become a little immune to the impossible.

The second adaptation of this story I watched was the 2001 BBC TV movie starring Bob Hoskins as Professor Challenger and boy! what a difference 75 years make. This version was obviously always going to be more accessible and with the special effects taken care of by the same team that produced the hugely popular Walking with Dinosaurs series (indeed, some creatures were used for both programmes), it was far more watchable and more entertaining entirely.

But is it as important a film as the earlier one? No, definitely not because as artistry in film goes, it is no better than average. In 1998 the Library of Congress selected the 1925 film for preservation in the US National Film Registry as being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant”, something that the BBC version will never be deemed. Perhaps one of the reasons it is less significant is that we all recognise the creatures to be computer generated, after all, ever since Steven Spielberg made Jurassic Park in ’93 (a film that will surely gain inclusion to the registry at some point), we’ve got used to seeing them this way. And let’s face it, they look about as real as we’d ever want them to

Let’s just suppose for a moment that Spielberg had dreamed up a hoax (perhaps a ‘market experiment’ would be a better term) sometime before the 93′ release of Jurassic Park and that hoax involved a crackpot professor with an outlandish story. This professor made headlines because he wanted to tell the world about some fantastic trip he had just returned from and he then proceeded to show the world footage of prehistoric beasts he had reputedly taken while there, footage which was actually pioneering computer-generated imagery of dinosaurs Spielberg had recently perfected. Would the world have been fooled? After all, we’d never seen anything like it before had we? Isn’t it just possible we would have reacted in the same way as Sam Neil’s Dr. Grant and his party when first encountering the Brachiosaurus in the movie – i.e. pinch me, I must be dreaming.

It’s hard to imagine now but in 1922, Arthur Conan Doyle showed a test reel of Willis O’Brien’s work to a meeting of The Society of American Magicians, one of whom was none other than Harry Houdini. The footage – which Doyle craftily refused to discuss the origins of – depicted a Stegosaurus, a family of Triceratops and an attack by an Allosaurus. The next day, the New York Times ran a front page article saying, “(Conan Doyle’s) monsters of the ancient world, or of the new world which he has discovered in the ether, were extraordinarily lifelike. If fakes, they were masterpieces”. You get my drift? If those magicians were fooled by something they’d never seen before, couldn’t we be? Or has the coming of the digital age, where any visual representation is possible and incredibly lifelike, robbed us of that mystique of the unknown? UFOs, Bigfoot, the Loch Ness monster – even if (for the sake of this argument) it were genuine, would even the clearest of film footage convince us nowadays?

There’s no denying special effects evolved enormously between The Lost World of 1922 and Jurassic Park of 1993 and in terms of lifelikeness these two examples are at opposing ends of the visual spectrum. But my God! didn’t it take a long time to get from one end to the other? The stop motion technique was refined and better filmed perhaps with the passing of decades (Ray Harryhausen will forever be a favourite of many) but it took 70 years for any groundbreaking improvement. And then, BAM! with the help of computers, suddenly we’re seeing monsters that don’t twitch when they move, suddenly we’re seeing dinosaurs that actually breath, that flow with their movements, that look, for want of a better adjective, REAL. And all this creativity and invention simply to make our visual experiences more lifelike and thrilling.

But where is the future? Most special effects are virtual reality now – that is, what we see on screen is virtually real – but it can never be ‘really’ real because it’s on screen and consequently not reality so again, I ask, where is the future? Where do filmmakers go from here? Let’s all be honest now and admit that apart from involuntarily ducking your head out of the way of some apparent incoming object, 3D doesn’t really add that much to the cinematic experience yet. Haptic technology such as that found in flight simulators and certain video games which simulate motion to the user by applying forces and vibrations is quite exciting but whether it will ever have a place in cinema is debatable. And yet there’s bound to be a continued progression – it’s simply the way of things. But who can see the road ahead?

Personally, ever since Jean Luc Picard and his crew occupied the bridge of the Enterprise in Star Trek The Next Generation, I’ve been looking forward to the arrival of the Holodeck. Surely, that’s the future right there. A room projecting an optical reality all around us in which we can interact with simulated people and objects and move around on a virtual treadmill. That’s got to be fun. Sadly though, if that’s going to take another 70 years to become fact, I’ll never know because I’d have gone the way of the dinosaurs.