I’ve said it before but I’ll say it again – I truly love it when I stumble across an old movie I’ve never seen before that blows my socks off. A few days ago, this 1951 Kirk Douglas crime drama did just that. Figuratively speaking, of course.

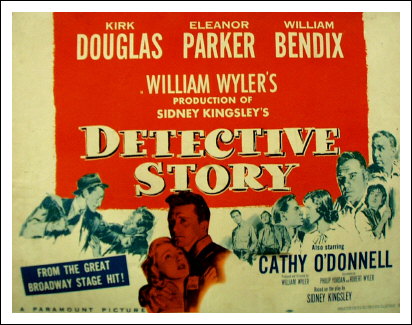

Detective Story is based on the stage play of the same name by 1934 Pulitzer Prize for Drama winner Sidney Kingsley and it’s directed by Roman Holiday and Ben-Hur legend, William Wyler.

By virtue of the story originally written for the stage, it’s a character study and in this case the character, or rather characters, are a squad room full of plain-clothed detectives at the 21st Precinct in New York City. The action takes place over the course of a working day and apart from a brief foray into the streets of the city, we remain confined within said squad room. We see the various detectives attending to their tasks – mundane police procedures included – as well as the various criminal elements that they apprehend that day. It’s all very gritty. But don’t misinterpret that as heavy going and oppressive, for it isn’t. Certainly not at the outset anyway. Yes, the tension builds to a dramatic climax, one that will take your breath away, but along the way there’s subtle humour and questions of morality too.

The main thrust of the plot involves, naturally enough, Kirk Douglas’s character – Detective James McLeod – and his wife Mary (Eleanor Parker) who just so happens to have a skeleton in her closet. McLeod is a tough, no-nonsense cop who sees the world he inhabits as black and white. You break the law, you pay the price. No leniency whatsoever. His current focus is on bringing down disgraced doctor Karl Schneider (George Macready) for having performed abortions on several women which subsequently lead to their deaths however, the more McLeod pursues the closer he gets to a truth that will turn his world upside down.

For the most part, this movie is a filmed stage play and as such there’s a degree of claustrophobia present in its viewing, perhaps even more so than if you were sitting in your theatre seat before the stage. Obviously, this sense of confinement is intentional because the film actually benefits from it. We are in a living, breathing squad room after all, and around us are all the individuals you’d expect to find there. Even when Lee Garmes’s camera lens pulls tight onto action in the foreground, the squad room’s heart still beats in the out-of-focus background. The company of actors, those playing the detectives and the criminals at least, are rarely off the set. It gives the whole thing an organic feel.

The acting – leads and support – is all round solid too. Douglas gives a towering performance as the cop who’s too unforgiving for his own good although oddly enough when it came to Oscar time, he was overlooked. Eleanor Parker got nominated, as did Lee Grant (in her big screen debut, no less) who plays a young shoplifter. There were also nominations for Best Director and Best Writing in the Screenplay category. Like Lee Grant, Joseph Wiseman, who plays a slightly unhinged burglar called Charley Gennini, was also performing for the first time in front of a movie camera. Wiseman would later go on to cinema immortality playing Dr. No, the first bad guy in a popular spy franchise. His performance here couldn’t be more different.

Like all good dramas, it’ll imprint traces of itself in your mind and you’ll be thinking about it long after the music has flourished and the credits have rolled.