Right, so tomorrow I am going to see the new James Bond movie, directed by Sam Mendes and starring Daniel Craig, Javier Bardem, Judy Dench and Ben Wishaw. It has garnished very good reviews so far but I have not read any of them. With this movie, I am not leaving anything to chance! I need to go in clear-minded and as neutral as I can be. I have read some interviews here and there but for some reason, I had no desire to know more than the snippets of information I got from the trailer and the few words exchanged by Mendes and Empire magazine. The story goes thus: Bond is accidentally shot by Naomi Harris on the roof of a train, he fakes his death to drink a lot and play with scorpions and Judy Dench has to write his eulogy. Then out of the blue, MI6 is compromised, bombed and sensitive information on all agents is leaked on YouTube. The man who did so is called Silva and has a major grudge against M, something Bond does not like so he returns to England to save the day. However he really looks old and weak. Is he a match for the evil Silva and is he brainwashed by M? What’s Skyfall? Who is Silva? Why is Q using realistic technology? Hmmmm…the questions seem to multiply as I type.

So what are my expectations on this movie? What Bond movie do I expect from this day and age? What things am I hoping they improved after Quantum of Solace?

I have a confession to make. I was never a Daniel Craig fan until very recently. When I saw he would take the mantle from a very confusing Pierce ‘Bond’ Brosnan (remember Die Another Day), I was very sceptical. Actually who the hell am I kidding? I hated the idea! I was absolutely repulsed at the guy. He was not handsome like Connery, he looked too old and too noticeable (in that he was built like a house). All that muscle seemed to somehow make his brain smaller by each passing frame. My mom used to describe the great Hercules as ‘All muscles and a brain like a sesame seed’. I am afraid my mind only screamed that saying when I saw Craig in the first shot of Casino Royale. And yes, I was one of those people that had something against the blonde hair! Yes, I, like a lot of people, am a creature of habit at times and when that habit is broken I start complaining. Like you can sit here, reading this, and tell me that never happened to you. Plus, I can say that the concept of a prequel depicting how Bond got his 00 status was not that intriguing to me. I was born and bred on Connery and Moore, already seasoned spies that have been in the fucking and killing business for a long time. Why would I want to see a character that had started so high in his career go down 10 levels and be a rube again? But then again, I pride myself in giving a second chance to anything that I feel I might have not understood or had disapproved of, from the start. I also pride myself in this particular case to have made the right decision. If not I would not be sitting here writing about Skyfall.

My Bond has always been Sean Connery. Primitive, smooth but not very discreet, resourceful, witty (but not as much as Moore) and seemingly motivated by selfish reasons. If you look at his missions they all seem to end up on a beach most of the time, kick-started by a girl or a photo of one (Dr. No, From Russia with Love, Thunderball) and not once has he shown any sign of actual patriotism. He did this for the fun of it and the kicks (chicks) he got out of it. His look defined a generation of spies. The tuxedo, the signature drink, the cigarette at the end of his lips as he utters his name, like it’s a gift from God (not him, just his name). He had the fighting skills to beat up his enemies, had the talent to land a falling plane safely (although Timothy Dalton took the whole plane stunt to a whole different level in The Living Daylights), attach himself to a harness and grab the girl before flying away thanks to a taxi-plane, had the luck to be let out of an incinerator just in time, and had a Nemesis in Ernst Stavro Blofeld, SPECTRE mastermind and bad guy to the bone! Not many Bond nemeses would come along later on that would be as amazing as this man. Meddling in Cold War relations, NATO nuclear missiles, the diamond business, stealing whole spaceships with another spaceship that is hidden in a fake volcano. The dedication alone is just beautiful. Shame he had to leave the stage so early on and in a less than adequate way for his persona(For Your Eyes Only).

After Connery, the forgotten and underrated George Lazenby took over, however I will be completely honest, he has not left any particular trademark as Bond. I was very young when I saw On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and was very sad that Bond got married, until the obvious little glitch on the way to the honeymoon. Lazenby was not a big part of my idea of Bond and realistically neither was Roger Moore. Something just did not sit right with me and his Safari suits, his little one liners and his weird missions. However, Moore had the immense privilege to be in films where the focus was put on the villains. Yep, all sorts of villains and megalomaniacs but hell, they were the pinnacle of sneaky, malicious, crazy, napoleonic figures and had the best henchmen. Don’t believe me? Let’s tally: Kananga and Baron Samedi (Live and Let Die), Fransisco Scaramanga and Nick Nack (The Man with the Golden Gun), Carl Stromberg and Jaws (The Spy who Loved Me), Hugo Drax and The Cat (Moonraker), Aristotle Kristatos and Locque (For your Eyes Only), Kamal Kahn and Gobinda (Octopussy) and finally Max Zorin and May Day (A View to A Kill). I remember all of them as clear as day; Hugo Drax setting the dogs on Corine Dufour, Jaws chewing some cable car wire in Rio, Nick Nack loyal to his master till the end, Gobinda crushing dice in his fist, reducing them to powder in front of a very worried Moore. If the Connery era defined the spy, the Moore era defined the villain.

Who combined both? My close favorite and the Bond I found the most gritty till Craig came along, Timothy Dalton. It took two movies and one Colombian drug lord to show that Dalton knew how to deal with trash. He fed rotten CIA agent Killifer to a great white shark and ignited Franz Sanchez to the sky to avenge his best friend. There was not that much dedication to avenging his dead wife was there? That’s probably because in the 80s there was no room for tact within a spy’s lifestyle. This was a time of violence and Timothy Dalton was the violent Bond. The one that looked like a remorseless killer, the darkest side of Bond yet. Brosnan took the darkness to the next level but his movies suffered from scripts that could not cope very well in the post-Cold War era. The last great Bond in my opinion can only be Tomorrow Never Dies because it contained a realistic Bond and an extremely plausible villain in Elliot Carver (read Rupert Murdoch. Huh? Who said that?). The death of Paris Carver shocked me when I first watched it, as well as the frigging monster of a man that killed her! It was also surprisingly the first Bond I ever saw in English because all the VHS copies we had at home were all dubbed in French. To this day I can quote you From Russia with Love in both English and French. Funny how that turned out!

Then came Craig. Following my six years of objecting, complaining and turning down all positive reviews about the actor’s portrayal, I looked at him differently. I scrapped all the Bonds from my mind and looked at a man, a spy, a borderline sociopath working for an organization that does not approve of him but believes in him (God bless you M) and battling the enemies of the country that trained him and made him a ghost for the rest of his life. Craig played just that. He played the man all of the previous Bonds could not play because of time, place and context. For every era comes a different hero and Daniel Craig successfully embodies this generation’s anti-hero with a heroic purpose.

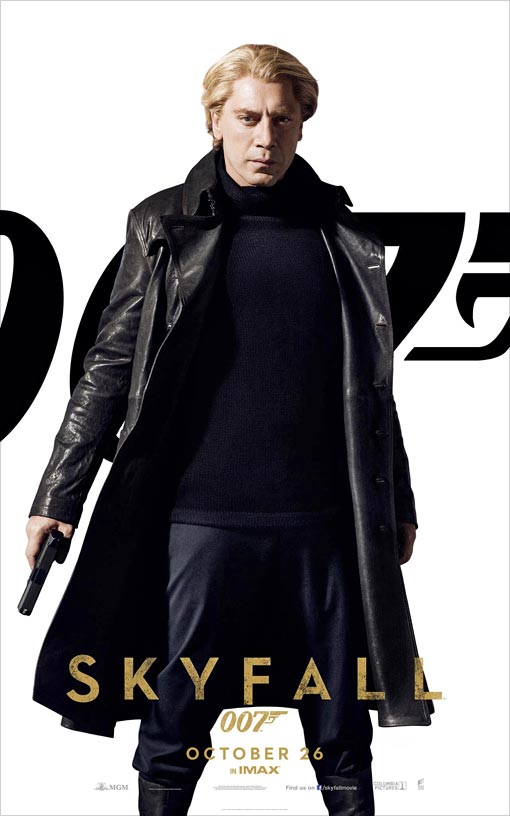

For Skyfall my expectations are simple. Craig’s Bond almost lost credibility with the latest outing but through no fault of his acting. Surrounding issues such as script, villain and Bond girl made this 007 chapter bearable but I expect Skyfall to take Casino Royale and transpose the major characteristics of the other movies. So far, the villain looks properly old-school and it helps that Bardem, like a lot of kids, grew up with Bond. If his villain reaches the charisma the previous ones had (namely Emilio Largo, Max Zorin, Franz Sanchez and Elliot Carver) then that would culminate to an unforgettable character like Ledger’s Joker in the latest Batman franchise. The arrival of a new Q deserves attention as well, since that means that this shit is about to get technological, something Craig’s movies have not explored yet. From the trailer, I am thinking Big Brother surveillance and tracking to get to Silva. M and MI6 look like they have a lot more secrets than a regular secretive agency and they all look human, prone the error (only their errors seem to have graver consequences than the regular Joe). This humanity culminates with Bond. I want to see him suffer, confused, double-crossed and run down, not for any other reason than to see him rise up from the ashes and stand, proud and angry. I do not hold much hope for the Bond girls. This seems to be a man’s adventure with little around him to distract him long enough from his ultimate goal. Finally, I expect from Mendes to turn this film into a thriller, fast-paced, structured, respectful of its genre and a film that you would want to see like you would want to see Dr.No, again and again. But this time Craig has to face real an present evil that would terrify you, me and the whole audience. I want a Bond you hate to love, a Bond that will laugh at his enemy because he does not care whether he lives or dies so long as he gets the last word! A Bond that represents this era of confusion, violence and fear, that he vanquishes through fire and blood, because in the end, it is the only way this current world deals with its evils.