I hope regular readers of my musings on this website will not react with a weary roll of their eyes when they see, once again, I’ve employed that timeworn word – “classic”. Though I suppose more than this, I actually hope there are regular readers of my musings on this website. Even just one. Or perhaps two or maybe even a handful. Well, being the optimist that I am – Hi, hello, thanks y’all for stopping by.

You see, the word “classic” gets bandied about all too often in my opinion. It seems to be used as an enticing adjective for anything that isn’t particularly young. Art, architecture, furniture, clothing styles, cars, literature, music – and so on. But surely, there’s more to it than mere age – after all we don’t say “his grandfather was a classic person” or “Hadrian’s Wall is a classic defensive fortification” do we? Not usually anyway. So what quality must be present for something to warrant the term “classic”? What does Cary Grant’s Savile Row suavity have in common with an original Jaguar E-Type? And what do they both have in common with New York’s Flatiron building? They are, after all, three things that could be described as being about as “classic” as you can get. Style and popularity? Yes and yes and certainly important. But age? Well okay, they’re all of the past but is that what defines them as classic? If the new iPhone 5 can be described as having classic styling, then surely age can be dismissed as being an influencing factor.

Perhaps all it comes down to is an initial opinion. The very first one. An opinion offered by an admirer who uses the term “classic” and the ears that hear that opinion agree and so the label sticks. I’m sure we can all summon something to our minds that has long held the “classic” monicker, something which we utterly abhor and deem totally unworthy and likewise on the other side of the coin something we hold dear that hasn’t garnered the label. If this should prove true for you, I suggest writing about it and giving it the label yourself, after all, the certification starts somewhere right? Did Khufu glance over the plans of his new pyramid and say to his chief architect, “Yes, it’s a classic design”? Maybe, maybe not.

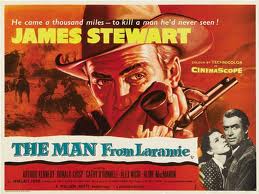

Anyway I digress. Back to The Man From Laramie – a CLASSIC western if ever there was one. This was the last of eight collaborations between the film’s star (the wonderful James Stewart) and its director (the sublimely gifted Anthony Mann) and five of those eight were westerns. Over the years, Hollywood has churned out thousands of these horse operas and “cowboys and indians” films, many of which would blush with guilt at having to live up to being called “average”. But there are a good number of watchable ones too and of course as we reach the higher levels of excellence and artistry the number diminishes significantly just as it does in any other genre. But these five Anthony Mann westerns (and by the way, I already reviewed another one of his some months ago, see The Tin Star) can, in my opinion at least, sit right up there with all but the elite, the creamiest of the creamiest, the royalty of the genre.

Sometimes it’s hard to define, to put into words why something works so well when the same ingredients were used elsewhere less successfully. While there are plenty of things that can be said about these five westerns – Winchester ’73 (1950), Bend Of The River (1952), The Naked Spur (1953), Far Country (1954) and The Man From Laramie (1955) – they are all sums of their parts with many things working together in harmony to create that perfect “whole”. Certainly Mann and Stewart were the main factors. In productivity terms, their partnership was as harmonised as Wayne’s and Ford’s, Bogart’s and Huston’s, Eastwood’s and Leone’s or for that matter, De Niro’s and Scorcese’s . For a start Stewart’s glittering star was at its peak throughout the 50s but a quick glance at Mann’s credits suggest that his value in Hollywood during that decade was substantial as well.

But let me get to the point. The Man From Laramie tells the story of Will Lockhart (Stewart) a former captain in the U.S. Army who rides into the isolated town of Coronado to deliver supplies from Laramie. He has a personal vendetta to fulfil while there – to search for and kill whoever is responsible for selling repeating rifles to the local Apache Indians, Apaches that attacked and murdered his brother at nearby Dutch Creek.

What he finds is a town run by ailing cattle baron Alec Waggoman (Donald Crisp), his worthless and vicious son Dave (Alex Nicol) and ranch foreman Vic Hansbro (Arthur Kennedy). Plus of course a pretty woman in the guise of Barbara Waggoman (Cathy O’Donnell). Lockhart’s presence soon stirs things up like a mongoose at a snake party and it’s not long before he’s having to stand up to Dave and Vic. He’s persuaded to take a job with neighbouring rancher Kate Canady (Aline MacMahon), which he does in order to stick around and continue his investigations but again he’s soon facing the vicious Dave, who this time maims Lockhart in a most cruel way. As Lockhart begins to unearth the truth behind the sale of the rifles to the Apaches, conflict threatens to destroy the guilty party from within.

The film builds familiar themes like greed and betrayal into a tense climax however don’t for one minute think that ‘familiar’ here means average. This film has been described as a western version of King Lear and whilst that might be stretching the facts a little, it’s quite easy to see that Mann was hinting at something Shakespearean. The actors who do the most work are all terrific but the prize for audience captivation has to go to Stewart for yet another performance of brooding intensity (The Naked Spur being another fine example). An actor once said of his style, “It’s not what I say that’s important, it’s what I don’t say,” – a sentence that fits Stewart’s portrayal of Lockhart perfectly. He makes you feel what he’s going through as much by reading what’s behind his eyes as by what comes out of his mouth. He’s awesome. But then, he is James Stewart.

The Man From Laramie was adapted from a story of the same name in The Saturday Evening Post by Thomas T. Flynn in 1954. It was also one of the first westerns to be filmed in CinemaScope, a technique used for shooting wide screen movies which was popular from 1953 to 1967. It certainly helped Anthony Mann capture those sweeping vistas of scenery, which was something of a trademark in his James Stewart westerns. In this case it was the arid brown landscape of New Mexico but in The Naked Spur is was the mountainous beauty of Colorado and Lone Pine, California. Check it out. On film, you’ll never see it look better.

While there may be better examples of this most American of genres, they would be the exception rather than the rule. Anthony Mann was a director who never really garnered the praise he deserved and for all his contributions to cinema, he never won any awards. He received a few nominations, a Golden Globe for El Cid and three Directors Guild of America awards for El Cid, Men in War and The Glenn Miller Story but he was overlooked completely when it came time to hand out the Oscars. And yet, his body of work is truly solid and includes crime dramas, musicals, comedies, biopics, action adventures, historical epics and of course westerns. And he rarely failed to tell a story well. For me though, it’s his five westerns made with James Stewart that immortalises him in the pantheon of the great moviemakers for they are as “classic” as anyone else’s you’d care to mention.