The spy film genre has been thrilling cinema audiences for over a century now and with certain franchises still flourishing, it’s likely to continue to do so for a while yet. Way before “Bond, James Bond” saved us from SPECTRE’s first attempt at world domination and even before the “talkies” allowed fans to hear their favourite actors’ voices, tales of espionage and government agents captured our collective imagination.

Like most (perhaps all) film genres, this one has its roots in literary works of fiction and these date back to a time shortly before the First World War when writers such a G.T. Chesney and William Le Queux imagined French or Russian invaders attacking Britain. As the fortunes of Europe’s major powers began to shift and colonial rivalries grew, new alliances were formed as new threats loomed and soon Germany became the number one foe in these literary tales.

Films like Peril of the Fleet (1909) and Lieutenant Rose and the Stolen Code (1911) tell of foreign attempts to attack the British Navy, the country’s single greatest defence against invasion. It’s interesting to note that in all these films leading up to the outbreak of WWI, the foreign spies are never given a country of origin because the films’ distributors were reluctant to close the door on a large cinema-going market. But once war had been declared, the enemy was named.

The genre grew even more popular during the 1930s when tensions once again began to rise in Europe and directors such as Alfred Hitchcock had many a hit with titles such as The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935) and Secret Agent (1936).

For many, the popularity of spy films peaked in the 1960s when the Cold War had pushed the bar of tension between east and west to its greatest height. This is where the action-packed adventure movie carved out a niche for itself and began to break box office records. Fantastical and ludicrous the plots may have been but in terms of entertainment, they were dynamite.

But there were also less stylised – but no less stylish – films being made, grittier, more realistic and equally suspenseful. Films like The Ipcress File (1965) and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) both adapted from gritty spy novels (Len Deighton and John le Carré respectively) were low on action but high on procedure and intrigue.

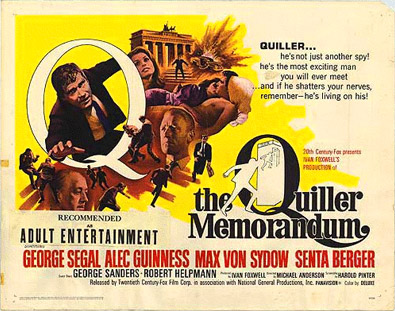

And so we come to The Quiller Memorandum from 1966 starring George Segal, Alec Guinness and Max von Sydow. A fine example of a grittier type of spy film this time set in West Berlin during the Cold War.

Quiller played by Segal is sent to Berlin by SIS (Secret Intelligence Service) to investigate the murders of two British agents by a mysterious neo-Nazi organisation. His controller there Pol (Guinness) warns him that a new generation of Nazis has emerged who are difficult to spot because they no longer wear uniforms. He orders Quiller to locate the organisation’s headquarters. With his only clues being three items found in the murdered British agent’s pockets, Quiller – clearly resourceful and laconic – sets out to do just that.

There is much shaking off of people following him and questioning people who may or may not have known the murdered agents – all simple investigative procedures – and yet the ever present threat in the perfectly photographed city (it was shot in Berlin) looms like an approaching storm. You feel as though Quiller’s every move is being watched by those he’s trying to investigate. The pacing is excellent and the tension builds nicely. And my God – it’s all so cool. Typical 60s cool but so subtly captured. The cars. The clothing. And John Barry’s superb soundtrack – surely nobody at this time was composing cooler film music.

Soon Quiller is captured by the neo-Nazi organisation and “persuaded” by means of a truth serum to tell their leader Oktober (von Sydow) the location of SIS HQ so that the bad guys can annihilate the good. Quiller may not be a musclebound tough guy but he’s nonetheless a tough nut to crack and he just about manages to deflect Oktober’s questioning so that Oktober, fed up with having his time wasted, orders him to be killed. But of course, he escapes his would be assassins and….no, that’s all I’ll say. Because it really is worth a look if you’re a fan of thoughtful spy dramas.

It was directed by Michael Anderson whose credits include The Dam Busters (1955) and Around the World in 80 Days (1956) and adapted by Harold Pinter from the 1965 novel The Berlin Memorandum by Elleston Trevor (under the pseudonym Adam Hall). It was nominated for three BAFTAs while Pinter was nominated for an Edgar Award but it failed to gain a win. But that really doesn’t matter.

My only complaint, if I could call it that? How the hell is it that I’d never seen it before last week! I’m amazed that such a classy spy flick had escaped my radar all these years. George Segal is perfectly cast as the quietly confident American who ends up with more trouble than he hoped as is Alec Guinness’s rigidly unemotional Pol, (he of course would eventually go on to play another spymaster character, George Smiley). Max von Sydow is suitably menacing as are his henchmen and Senta Berger (the love interest, of course) is wonderfully enigmatic and oh so alluring.

A very nice and sadly underrated film that is quite likely closer to how it really was than the majority of spy films ever made.