It’s fitting that I bring this movie up now because as I’m sure anyone who’s watched the news or read a newspaper this last week will realise, today is the 70th anniversary of this most indelible event.

6 June 1944. D-Day. The commencement of the Normandy landings and the subsequent Allied invasion of Normandy. It remains the largest seaborne invasion in history and it led to the restoration of the French Republic and the defeat of Nazi Germany.

With even the youngest of veterans from the Normandy campaign now being in their late 80s, it’s perhaps little wonder that the number of those making the pilgrimage across the channel this year for the 70th anniversary has prompted the Normandy Veterans Association to declare this their final official commemoration of the event. It plans to disband in November owing to dwindling numbers and the increased difficulty of its remaining members to travel. The association, which was set up in the 1980s, had 16,000 members by the 1990s however, five years ago that number had fallen to around 4,500 and now the number is closer to 600. And while this is sad but ultimately inevitable, I don’t imagine it will be the end of our commemorating this epic undertaking. And epic it was.

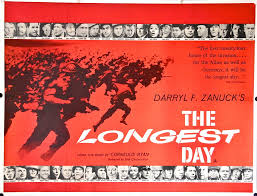

While The Longest Day may be a flawed movie, it does a fair job of depicting the scale of the operation. It was, after all, a multi-national effort on behalf of the Allies and required careful coordination between all three branches of the armed forces, as well as the French resistance networks. There are many threads running through the near three hour run time showing us as much detail of the operation as time allows. We see numerous individual companies and battalions tasked with their own objectives, the success of each one vital to the next. We see the efforts of the Resistance putting explosives to good use and we also get a perspective from the German side which shows us that some incompetence on their part undoubtably contributed to the final outcome. The truth is (and this is where there are literally hundreds of fascinating individual stories), if it weren’t for a whole host of other factors such as sabotage by the Resistance, misinformation (planned by an organisation called the London Controlling Section) and bad decision making by the Nazis the outcome could have been very different.

Indeed to properly appreciate the complexities of the battle of Normandy would mean to remember everything (and everyone involved) that happened from the moment a cross channel invasion had been given the go ahead at the Trident Conference in Washington in May 1943 to the Liberation of Paris on 25 August 1944.

But this film is limited to the 6th June. D-Day. The Longest Day.

One of the film’s tag-lines reads – 42 International Stars!

And it’s not difficult to name them as they appear on screen – Henry Fonda, Robert Ryan, John Wayne, Richard Burton, Sean Connery…etc, etc. The list really does go on. And on.

But for me, the stars (and let’s not forget some of them actually fought in WWII) are less important than the story itself. Having said that, if you want to watch a serious account of D-Day, you’ll really have to watch a documentary of which I’m sure there are plenty. You could even go one step further and plan a visit, take in a museum or two and put yourself on the same ground that saw that terrible action all those years ago. Trust me, it meddles with your emotions.

Okay, so this is part film review and part a salute to what was undoubtably one of the most important operations of the entire Second World War. But a film review it is, so…

With the help of four other writers, The Longest Day was adapted for the screen by Cornelius Ryan from his own book of the same name which had been an instant hit upon release in 1959. Ryan was an Irish journalist and author of several books on World War II whose interest in the D-Day invasion began during a trip to Normandy in 1949. He also wrote A Bridge Too Far in 1974 which was given the movie treatment in ’77.

The Longest Day had no less than five directors, each responsible for a particular section. Ken Annakin directed the British and French exteriors, Andrew Marton, the American exteriors, Gerd Oswald, the parachute drop and Bernard Wicki, the German scenes. Producer Darryl F. Zanuck was an uncredited fifth director.

Because it was made only 18 years after the actual events portrayed, many of those who participated were still alive and therefore the producers employed several generals and high-ranking officers from both sides as military consultants. Curiously, one of them was Lucie Rommel, widow of Erwin Rommel. It won Oscars for Black and White Cinematography and Special Effects and was nominated thrice more.

The film divides opinion. Some like it, some loathe it. There are others movies (and an excellent HBO TV series) that depict D-Day and they may be more explicit and graphic in their action but they aren’t as concentrated on that fateful day and therefore don’t quite capture the immensity of the event.

That these 80 and 90 year old heroes continue to return to the northern shores of France, to the scenes that shaped the rest of their lives and likely still haunt their dreams is nothing short of inspiring. Many of them are accompanied by their families and friends, younger people who will hopefully keep the spirit of the campaign alive for generations to come.

Yesterday a TV reporter asked one of the veterans why he feels the need to keep coming back and as the old soldier’s voice cracked and his eyes pooled, he replied that he comes back to pay his respects to the friends that fell beside him and all those others who didn’t make it home.

God bless them all.