Gun Control: A Viewpoint

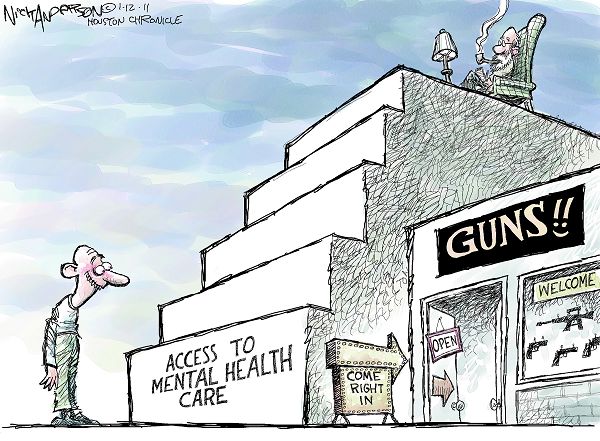

Three things happen when America hosts another gun massacre. Firstly, the rest of the world groans, “Really? Again?”, secondly, the NRA races to a media podium to declare that guns aren’t the problem, and thirdly, sensible people speak up and acknowledge that something needs to be done. Of course, what makes discussion particularly difficult is that gun control is an issue we automatically judge with emotions, but which needs objective analysis.

Most of the time, nothing happens. The ruling president will announce his sympathies and mutter that action must be taken to protect the innocent Americans, and then it’s business as usual. Newtown, however, seems to have been the straw that broke the camel’s back, as President Obama has announced that he will be taking action. Pleasing to many, the decision has also upset the NRA and many pro-gun folk, on the assumption that this is Obama showing his true self of wanting to oppress the American people and, so the hyperbole goes, essentially frog-march the people to concentration camps for Holocaust II.

We are told that the Jews were disarmed first, and thus, by default, if Americans can keep their guns they will remain safe from their government; that the government and military are unable to take the people over if they have their guns. The necessary logical fallacy here is the huge disproportion between what weaponry the Nazis had compared to modern day America – after all, the American military is the biggest in the world (a fact that America is always boasting), and its job, for which the soldiers are, ironically, routinely praised by the military-phobic public, is to take over other countries and fight armies. I wouldn’t imagine the nation with the crown of the World’s Fattest is going to stand much of a chance, M4 or no M4. The American military has drones, stealth bombers, tanks, rockets, Kevlar and, well, basically the tools and training to engage in warfare to succeed at the end-goal – which means the American public would have no chance of surviving a takeover if the government truly wanted it, with or without guns.

There also seems to be an attitude of defeat in the minds of many Americans; that yes, these massacres are tragic, but nothing can be done about it. As someone told me after Newtown on Twitter: “If Jesus could’t [sic] stop from being crucified then the world will always have nut jobs No law will ever stop a psychopath”. We’ll sidestep the theological problem, that ‘Jesus was sent to earth to die, and in doing so fulfilled his purpose’, and instead rebut with two simple facts: countries with gun bans suffer almost no gun deaths, and America has more guns and more gun violence than any other developed nation.

Those facts are swept aside much of the time though, and the party line from the pro-gun side of the debate is that if more people have guns, less people will use guns. The logical mind would simply assert that actually, if the criminal is pointing a gun at your face, he isn’t going to permit you the opportunity of getting your own gun out of its holster to protect yourself. In other words, criminals will always pull their guns first, and the law-abiding innocent will always be on the back foot. Indeed, if the country became one where everyone had guns, criminals would just aspire to be the most aggressive, the most heavily armed people on the streets – by their very nature, criminals will be willing to go further than the common citizen and they will always exist; America’s Gold Rush and prohibition history tell us that criminals exist and operate even under threat of murder by other criminals. Nonetheless, there was a loud declaration post-Newtown that teachers should be armed, and they can then kill any would-be mass murderer. Aside from the obvious difficulties that would pose, is turning back the clock to America emerging once again as the Wild West really what people want to see? Should children have to go to school with an omnipresent reminder to fear violence and death each and every day? There is an inherent problem with the idea that only “crazy” people shoot people: the reality is anyone can snap – and that problem is exacerbated when a gun is at hand. What happens if one teacher (and of the millions in America, the odds are strong that it will happen) shoots a child, will the Republicans be rallying that children themselves carry guns, so they can protect themselves?

The pro-gun side is also quick to say that overall gun violence has decreased over the past decade, but, of the 12 deadliest shootings in American history, six have taken place within the past five years. Since Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords was shot in Tucson in 2009 there have been 65 mass shootings; there were 10,000 firearm murders in 2011 – at a rate on the increase – and most of the developed world’s worst mass shootings have occurred in the USA. Figures like that would suggest to any reasonable mind that the situation needs amending, but instead we’re greeted with this line: “Anyone who wants to ban guns supports the rape and murder of women and children.” Of course, one could easily respond with, “Anyone who doesn’t support gun control supports the near-constant firearm homicides and injuries of innocent people, as well as the slaughter of children.” Both statements represent extremist views.

Surely the answer lays somewhere in the middle, but we’re told to reject any measure, because it is all a slippery slope to total eradication of firearms held by the American public. There’s no denying that there are groups who want a gun-free America, but the NRA is one of the biggest lobbying groups in the nation. That means that eradicating guns will not be as simple as some people seem to think it would be – because the opposite is big, rich, and powerful. What most people in the gun-control camp really want is sensible restrictions – and in a country where an assault rifle is cheaper than an iPad and less restricted than car ownership, there are numerous options that can be explored.

The pro-gun side often points to Switzerland as proof that a well-armed country has lower crime rates (although Switzerland could equally point to the USA as proof that a well-armed country has higher crime rates), but what isn’t taken into account is how Switzerland regulates its guns. For instance, most men are conscripted into the military at the age of 20, as Switzerland has no dedicated army it is formed by the civilians. Time in the military includes weapons training, as well as psychological tests. To purchase a firearm in a shop, buyers need weapon acquisition permits, with which a buyer can purchase three guns. When buying a gun from an individual, Swiss rules state that a permit is still required, and the seller is expected to establish reasonable certainty that the buyer is of a sound and stable mind. There must be a written contract between both parties, detailing the weapon type, manufacturer and serial number, and both parties keep the contract for a decade. Automatic and selective fire weapons are forbidden except to those with a special permit, obtainable by the cantonal police, and it can be acquired only when additional requirements have been met, such as owning a specific type of gun locker. In addition, every gun needs to be marked with a registered serial number, and a gun carrying permit is necessary to carry a loaded gun out of the home – and these are usually only issued to people working in such occupations as security. Switzerland also requires State agencies to maintain records of the storage and movement of all guns and ammo.

In short, Switzerland does not freely allow the purchase of guns but instead goes to great lengths to ensure that owners are responsible and able to own a gun properly. In America, there is no limitation on private sale, weapons training is not necessary to own a gun, no tests are undertaken to prove the person is of a sound mind, there are no records of the movement of weapons, and no lockers or safes are required in the home. Any of these provisions would be “gun control”, but may help to reduce the number of firearm murders and mass shootings. There are weak rebuttals to the idea of controls as being “unconstitutional”. That same argument overlooks that it is already illegal to own such things as tanks, rocket launchers and automatic weapons, and would mean it is unconstitutional to have the age restrictions and background checks already in place, but would many Americans truly feel comfortable removing those provisions? And if not, if it’s agreed that those measures are warranted, then there is no reason why a few more cannot be enacted – because ultimately, Switzerland shows that strong provisions work, and its gun ownership is not particularly restricted, rather the government knows who has what gun at any moment in time, and the owner must be mentally stable. That seems reasonable enough to a rational mind. Constitutionally, the right is to own guns, and all the while Americans are able to own at least one type of gun, the Constitution is not being overruled.

Guns do not need to be banned entirely, and the pro-gun camp is probably right that at this juncture in American history, there are too many guns on the streets for the average citizen to want to give them up and still feel safe from criminals. However, by borrowing some sensible precautions from Switzerland, America will be able to enjoy gun ownership and a higher degree of personal safety from those with guns. But if there is one stark fact, it is that the NRA and its advocates need to be bringing suggestions to the table; the ground is shrinking beneath their feet and each time they declare there is no gun problem in the wake of a massacre, they further alienate their stance. The line that guns don’t kill people, people kill people, may be factually true but it is simultaneously dishonest. The reason being that guns make it so much easier to take a life, or multiple lives, and other weapons – a knife, for instance – lack the same potential for disaster. That statement was demonstrably proved accurate on the same day as the Newtown massacre, when a man stabbed 22 children in school. Not one of his victims died, but each and every one of Adam Lanza’s Newtown victims were killed, thanks to the efficiency of firearms. That stark fact alone should be enough to demonstrate a need for change.

Interview: C J Stone

C J Stone is something of a literary heavyweight, with four books under his belt and former columns in such media outlets as the Guardian and Mixmag. So it with great pleasure that we welcome him to The Daily Opinion, where Lizzie Wright puts him under the spotlight. You can also read her review of The Trials of Arthur here.

What made you and Arthur decide to write this book and what did you hope to achieve with it?

I’d wanted to write a book about Arthur ever since I first heard about him in 1996. It seemed such an unlikely and at the same time inspiring tale. Unfortunately I wasn’t able to get a book deal for the project then. However, in 1999 I had just started to write a book about the protest movement of the time, and approached HarperCollins with the idea. It just so happened that Arthur had also approached HarperCollins and, as the editor already knew of my work, she decided to ask me to complete Arthur’s book for him. This was the origin of the book, The Trials of Arthur: The Life and Times of a Modern Day King originally published by Thorsons/Element (an imprint of HarperCollins) in 2003. The Trials of Arthur: Revised Edition, which you are reviewing here, is a heavily rewritten version of that book.

Arthur and I met the editor, Louise McNamara in September 1999 and we discussed what we wanted to get out of the project then. Arthur described it in these words: “If I can do it, anyone can!” In a sense you can take this as the motto. If some dysfunctional kid from a council estate can transform himself in such a memorable and dramatic way and make a real difference to the world, then so can any one else. Thus it is a book about someone writing their own story in life and making it come true.

For me the initial project remains. It is still a book – perhaps THE definitive book – about the protest movement of the 1990s, but using Arthur’s story as the thread around which everything else is woven. So it contains, amongst other things, the history of the road protest movement, the history of the Stonehenge campaign, the history of Reclaim the Streets and the history of the various mobilisations against the Criminal Justice Act in 1995 & 1996. It also includes a history of the neo-pagan movement, and a history of bikers, plus there’s a bit of my own history too, of how I came to meet Arthur.

You’ve written in a tone that makes the book accessible to anyone, but who was your initial target audience?

We wanted the book to be accessible to anyone, and while we had a core audience in mind (protesters, pagans, druids, bikers, hippies, and anyone interested in alternative culture) we also wanted it to be read by the general population. It’s a book about changing the world, but the world will never change until everyone gets involved.

Was there anything that you left out from either your or Arthur’s life that you would have loved to include?

The book ends in the year 2000 with public access to the Stonehenge monument having been reinstated, so anything that has happened since then is missing. Obviously Arthur hasn’t stopped there, and there have been many campaigns since, but the book would never have ended and the 2000 cut off date seemed appropriate. Also Arthur and I had many adventures during the writing of the book which never made it in to the final text: like the time we went to the Faslane Peace Camp near Glasgow with Mog Ur Kreb Dragonrider and met a man who thinks he’s John the Baptist and Arthur got himself arrested, or the time when I ended up sleeping in a bin outside Countess Services near Amesbury.

You can read those stories here: http://christopherjamesstone.wordpress.com/2012/11/19/the-trials-of-arthur-revised-edition-is-a-brand-new-book/

The overall tone is one of joy and contentment. Did you have to change your view of more painful events to maintain this tone?

It’s interesting you should use the words “joy and contentment” to describe the tone of the book. I’m not sure that was the intention. Certainly it is a very funny book in places. You couldn’t go round in a white dress calling yourself King Arthur without arousing plenty of laughter. That is one of Arthur’s greatest traits, his ability to laugh at himself. Without it you would inevitably have dismissed him as a loony. The joy of the book – which I agree is there – is in its unwavering commitment to challenging the forces of repression. Standing up for what is right, although it is hard at times, always leads to a feeling of joy. But “contentment”? I’ll accept that it is there as you have felt it, but I can only explain it as the inevitable consequence of the writer, me, doing what he loves the most, i.e. writing. As for painful events, well there were many, of course, but being able to laugh at them is one of our human characteristics and I wouldn’t be human if I didn’t like to have a laugh.

What was the writing process like? Did you and Arthur reminisce as you wrote or was there a strict outline that you followed?

It was quite hard at first trying to get an effective working method, and the book took much longer to write than either Arthur or I had expected (much to Arthur’s frustration at times). We decided to use the first person plural (“we”) as the narrative voice at an early meeting, and later Arthur came down to my home town and we worked out the structure of the book between us. After that I would ring Arthur up and we would have long conversations during which I would take notes. At other times I would set Arthur writing tasks, getting him to describe certain people or certain events in his own words, so there is a lot of Arthur’s own writing embedded in the text. There are also two complete chapters that are entirely Arthur’s, and no part of the book went ahead without us discussing it and agreeing on it. Arthur says now that we had many arguments during the writing of the book, and I guess this is true, but in the end we worked together remarkably well I think, considering that we are both complete egotists.

Although you portray the world of King Arthur through very understanding eyes, did you come across many sceptics who could not understand it?

You’ll see from the above link that I had a lot of trouble with this. It wasn’t people’s scepticism that worried me (I’m a professional sceptic myself) it was their downright hostility. One of my main antagonists during the writing of the book, who made it a personal quest to ridicule the whole project, died of alcohol poisoning in the Philippines, so you have to ask which of us had more of a grip on reality. Also, as I’ve often pointed out, if you look at the state of our current world, and then compare that to what Arthur is doing, which would you judge to be the sanest and most down-to-earth? I know which one I would choose.

The world of The Trials of Arthur is very different and more restrictive today. What would your advice be to young adults reading your book?

Is the world more restrictive today? Yes, you might be right. But that’s the point about Arthur and me, we never took those restrictions as inevitable. My advice is to follow Arthur’s philosophy and to “go for it”. Remember, the restrictions that are placed upon you are man-made and can always be challenged. That is Arthur’s lesson. One of the stories he likes to tell is the one about the custody sergeant at Salisbury gaol. Every year from 1990 till 2000 Arthur would step through the four mile exclusion zone which the powers-that-be had placed around Stonehenge on the solstice and get himself arrested. He was taking on the British government, the police, the law, the landowners, the entire might of the British establishment. So every year he would end up in Salisbury nick, and every year the custody sergeant would say, “you’ll never win you know Arthur,” and Arthur would say, “you just wait and see whether I win or not.” Well we all know now who was right now that open access to Stonehenge has been reinstated and Arthur no longer has to spend solstice night in Salisbury gaol. Let that be the lesson. Never give up. You may not always win, but, as sure as damn it, if you do give up you will be certain to lose.

Yours and Arthur’s journeys are far from finished. Will there be another book about them?

Arthur and I will always be friends, and, no doubt, there will be other writing projects involving him in the future, but, for now I’d like to say that this particular project is finished. It was started in 1999 and the first version of the book came out on 2003, but I was never happy with the result. I only really completed the book to my satisfaction in 2012, so it has been a long hard haul. Thirteen years of hard labour. I’m happy with the end result – I can honestly say it’s a great book – but I really need to move on now.

Writing has obviously been a major part of your life. Who are your literary influences?

There are many, but, just to name a few: William Golding, particularly an obscure but fascinating book called Free Fall, which came out in 1959. I’ve reread it several times and I would recommend it to anyone. After that it was Kurt Vonnegut, whose style I have flagrantly stolen. If you want to know what a good book should read like, then you couldn’t do better than taking a look at Kurt Vonnegut. After that it was Robert Anton Wilson who wrote the Cosmic Trigger trilogy, and Prometheus Rising, both of which I would recommend. I also like the historians, EP Thompson, Christopher Hill and Eric Hobsbawn, but my most consistent influence has to be William Blake, particularly the Marriage of Heaven and Hell, which I’ve read and reread countless times, and which still offers new insights every time I look into it. You have to read the facsimile edition, however, to get the best out of it. It was designed as a work of art, and you need to look at the images as well reading the words. It is a book whose central meaning will never die.

The Trials of Arthur: The Life & Times of a Modern Day King – CJ Stone and Arthur Pendragon

It if fair to say that this book is unlike any other that I have read and that alone is a good enough reason to give it a try. It depicts the inspiring and unique journey of Arthur Pendragon, also known by numerous other names, as he discovered his true calling in life. To begin with I was worried that this might be an overly didactic tale of King Arthur in the 21st Century, but I was greatly mistaken. The Trials of Arthur is simply that: an insight into his life as he transformed from squaddie to biker to King Arthur himself and everything in between. It is also a humble explanation of the difference that he made to those around him, access to Stonehenge and to the world.

CJ has set the tone of this book perfectly. At no point do you feel like you are hearing the dreary tale of an eccentric man’s life. Instead it feels as though you are sitting around a campfire with Arthur and CJ exchanging stories and really getting to know these two extraordinary men. It is a gently humorous insight into the inner world of a misfit with a joyful rhythm propelling the story along. CJ explains not only the thinking behind each action, but also the sentiment, which ensures that the reader is never left behind.

The Trials of Arthur makes you stand back and take a look at your life, asking if you are happy and if you are making a difference for what you believe in. It doesn’t tell you what to believe, it simply says stand up for it. You gain an insight into the life of a Druid, but it is written in a way that simply allows you to accept that life, accept this man who believes that he is the legendary King Arthur. At no point did I think to myself ‘what a madman’. I just accepted what he believed and was inspired by his determination. The fact that one man, standing in the rain in his tatty leathers day after day, trying to persuade people that they needn’t pay to see Stonehenge, that it was in fact their right to see it, can influence so many people and ultimately lead to the end of restricted access to the monument, is truly inspiring. Overall this is a well written, humorous and insightful book, no matter what your personal beliefs might be.

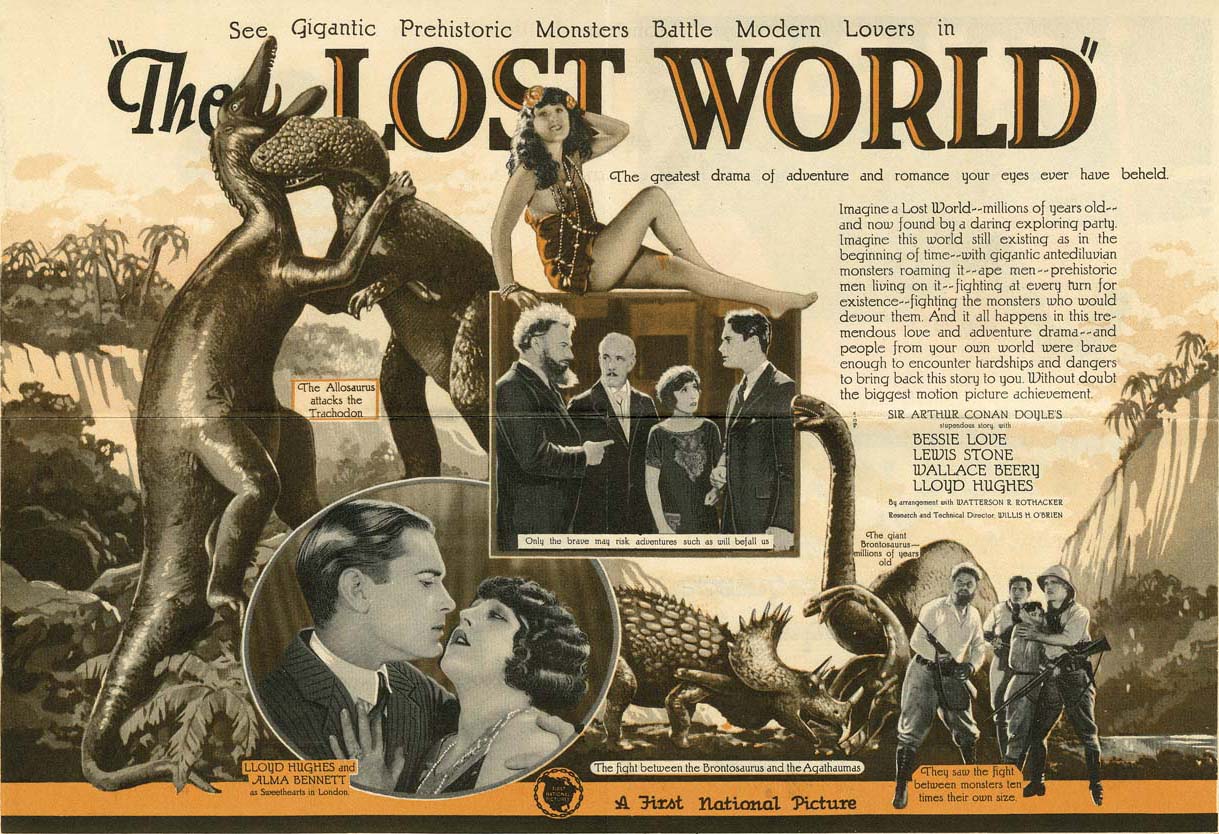

The Lost World

A couple of weeks ago, a well-thumbed copy of Arthur Conan Doyle’s classic 1912 novel The Lost World caught my eye on a bookshelf. Having read and enjoyed at one time or another similar tales of adventure by the likes of Jules Verne and Edgar Rice Burroughs, I took it down and indulged myself. I’ve had great pleasure in reading the majority of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories so therefore I felt certain I was going to enjoy this too. And enjoy it I did. The mix of Victorian characters, exotic adventure and prehistoric fantasy all written with that turn-of-the-century eloquence made it an eminently pleasurable page-turner.

Naturally, upon completion it led me to check out the original filmed version of the story which in turn led me to a comparison with a contemporary one. The first, directed by Harry Hoyt, was made in 1925 and the date of this alone is impressive, not least because this was still the silent era of cinema. One can almost imagine those early studio bosses scratching their heads and wondering how on earth do you take prehistoric beasts off of the page and bring them to life before a paying audience.

The answer was, of course, stop motion special effects and this was the first feature film to use such a technique courtesy of, in this instance, Willis O’Brien. O’Brien was a pioneer of this style of special effects and would become responsible for some of the best-known images in the history of cinema, his best known work perhaps being the greatest monster movie of them all, King Kong (1933). For audiences of the time, it must have been incredible to see dinosaurs moving about on screen when all they had ever seen of them before were drawings on a page. The film itself is significant for this reason and overall it’s worth a viewing not just to see how far cinema has come since those early days but also to see how creative these filmmakers were with the resources they then had.

In the film, Wallace Beery plays the brusque Professor Challenger who leads a group of British explorers into the Amazon in order to prove to the world that a land of prehistoric creatures exists on an isolated plateau. The South American jungle is depicted by set pieces of rainforest and river with the occasional snake dangling from a tree and one or two cutaways to stock footage of a snarling jaguar. The prehistoric plateau is more of the same but with models of distant smoking volcanos and of dinosaurs roaming around or fighting in that uniquely disjointed way that is stop motion animation. One panoramic scene of dozens of dinosaurs fleeing an erupting volcano was created on a tabletop that was 150 ft long by 75 ft wide!

By today’s standards it is, of course, laughably crude but then in this digital age where everything from men made out of liquid metal to flying vampires can be brought to life so convincingly, we’ve all become a little immune to the impossible.

The second adaptation of this story I watched was the 2001 BBC TV movie starring Bob Hoskins as Professor Challenger and boy! what a difference 75 years make. This version was obviously always going to be more accessible and with the special effects taken care of by the same team that produced the hugely popular Walking with Dinosaurs series (indeed, some creatures were used for both programmes), it was far more watchable and more entertaining entirely.

But is it as important a film as the earlier one? No, definitely not because as artistry in film goes, it is no better than average. In 1998 the Library of Congress selected the 1925 film for preservation in the US National Film Registry as being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant”, something that the BBC version will never be deemed. Perhaps one of the reasons it is less significant is that we all recognise the creatures to be computer generated, after all, ever since Steven Spielberg made Jurassic Park in ’93 (a film that will surely gain inclusion to the registry at some point), we’ve got used to seeing them this way. And let’s face it, they look about as real as we’d ever want them to

Let’s just suppose for a moment that Spielberg had dreamed up a hoax (perhaps a ‘market experiment’ would be a better term) sometime before the 93′ release of Jurassic Park and that hoax involved a crackpot professor with an outlandish story. This professor made headlines because he wanted to tell the world about some fantastic trip he had just returned from and he then proceeded to show the world footage of prehistoric beasts he had reputedly taken while there, footage which was actually pioneering computer-generated imagery of dinosaurs Spielberg had recently perfected. Would the world have been fooled? After all, we’d never seen anything like it before had we? Isn’t it just possible we would have reacted in the same way as Sam Neil’s Dr. Grant and his party when first encountering the Brachiosaurus in the movie – i.e. pinch me, I must be dreaming.

It’s hard to imagine now but in 1922, Arthur Conan Doyle showed a test reel of Willis O’Brien’s work to a meeting of The Society of American Magicians, one of whom was none other than Harry Houdini. The footage – which Doyle craftily refused to discuss the origins of – depicted a Stegosaurus, a family of Triceratops and an attack by an Allosaurus. The next day, the New York Times ran a front page article saying, “(Conan Doyle’s) monsters of the ancient world, or of the new world which he has discovered in the ether, were extraordinarily lifelike. If fakes, they were masterpieces”. You get my drift? If those magicians were fooled by something they’d never seen before, couldn’t we be? Or has the coming of the digital age, where any visual representation is possible and incredibly lifelike, robbed us of that mystique of the unknown? UFOs, Bigfoot, the Loch Ness monster – even if (for the sake of this argument) it were genuine, would even the clearest of film footage convince us nowadays?

There’s no denying special effects evolved enormously between The Lost World of 1922 and Jurassic Park of 1993 and in terms of lifelikeness these two examples are at opposing ends of the visual spectrum. But my God! didn’t it take a long time to get from one end to the other? The stop motion technique was refined and better filmed perhaps with the passing of decades (Ray Harryhausen will forever be a favourite of many) but it took 70 years for any groundbreaking improvement. And then, BAM! with the help of computers, suddenly we’re seeing monsters that don’t twitch when they move, suddenly we’re seeing dinosaurs that actually breath, that flow with their movements, that look, for want of a better adjective, REAL. And all this creativity and invention simply to make our visual experiences more lifelike and thrilling.

But where is the future? Most special effects are virtual reality now – that is, what we see on screen is virtually real – but it can never be ‘really’ real because it’s on screen and consequently not reality so again, I ask, where is the future? Where do filmmakers go from here? Let’s all be honest now and admit that apart from involuntarily ducking your head out of the way of some apparent incoming object, 3D doesn’t really add that much to the cinematic experience yet. Haptic technology such as that found in flight simulators and certain video games which simulate motion to the user by applying forces and vibrations is quite exciting but whether it will ever have a place in cinema is debatable. And yet there’s bound to be a continued progression – it’s simply the way of things. But who can see the road ahead?

Personally, ever since Jean Luc Picard and his crew occupied the bridge of the Enterprise in Star Trek The Next Generation, I’ve been looking forward to the arrival of the Holodeck. Surely, that’s the future right there. A room projecting an optical reality all around us in which we can interact with simulated people and objects and move around on a virtual treadmill. That’s got to be fun. Sadly though, if that’s going to take another 70 years to become fact, I’ll never know because I’d have gone the way of the dinosaurs.

The War That Never Ends

“What is the fundamental question one must ask of the world? I would think and posit many things, but the answer was always the same: Why is the child crying?”

—Alice Walker

(Possessing the Secret of Joy)

His name was Ahmed Younis Khader Abu Daqqa. He was Palestinian; he was Gazan; he was human. He was the first of 30 children killed by Israeli attacks on Gaza in the space of just 11 days last November. He – like all the others – stood no chance: a 13-year-old boy with weapons no more deadly than the football he was playing with, shot in the stomach. Such ‘surgical precision,’ such care!

It’s only weeks after these events that I feel able to write about them with any sort of cogency. Even now, I only have questions: Who are the terrorists here? Which is the ‘rogue nation’? Where has the morality gone? It’s time for Israel to be held to account – fairly but frankly – not just by its enemies but by its friends too. Mindless, juvenile apology for an Occupation-addled junkie won’t get us anywhere. But that’s what you get when you’re brought up on a diet of indoctrination and half-truths.

Let’s get some facts straight. Since September 2000, 1,638 children have died in the fighting – 92 per cent (1,509) were Palestinian. From 13th until 19th November 2012, the IDF claims that 2,198 missiles were fired from both sides put together – 61 per cent of these (1,350) were Israeli. At a minimum estimate, 166 people were killed in last month’s episode – 96 per cent (at least 160) were Palestinian. The figures don’t lie.

There hasn’t been nearly enough contrition – not from Israel itself, and not from its apologists. “If we don’t support Israel, who will?” they say. Such an attitude is a double perfidy: of the principles a state of Israel should be held to, and of those dead, dying and to die (on both sides) because of the perversion of them. Resisting the automatic urge to leap straight to the defence of a country whose brain-washing machine is so slick that it would have us believe that the whole world is perpetually against ‘us’ is by no means easy for any Jew. But we must at least try. After all, the more in touch you are with the Jewish story of persecution, the more repulsed you should be by the day-to-day suffering, degradation and brutality to which the Palestinians are subjected. As Noam Chomsky notes, the “images of terror and destruction, and the character of the conflict, leave few remaining shreds of credibility to the self-declared ‘most moral army in the world,’ at least among people with eyes open.”

It’s the zealotry that’s blind to this fact that worries me most. It doesn’t insulate Israel as its proponents believe; it just pushes it down a path of mind-warping self-delusion. And it pushes us into constructing a frankly sickening fiction. ‘We’ are defending ourselves; ‘they’ are attacking. If citizens are killed, we can blame Hamas for hiding behind them – even though Gaza’s population density of 12,216 people per square mile renders this practically unavoidable. If international lawmakers or the media condemn Israel’s actions, we can cry “persecution!” and “anti-Semitism!” to our heart’s content – even though the reality is that we would never think, for instance, to ignore, exonerate or defend any other nation’s killing of 30 children in less than a fortnight. We should instead step back – in this as in so many other previous situations – and wonder what has gone wrong: Can this really be collateral damage? Is this self-defence?

Well, if it is, then count me out. For even to begin to excuse such atrocities is to make a claim that no empathic human being could: that fidelity to Israel and/or Judaism comes first – before any obligations to supranational legal parameters and before any duties owed to others on the grounds of common humanity. And that is something that I, for one, cannot and will not do. To ignore the standards by which we as a global community choose to judge one another is to assert some external claim (or rather, I might suggest, a divine claim) to superiority. To disavow responsibility for the fates of one’s fellow human beings is to toss morality aside. To support a set of ideals, whether religious, political or otherwise, without proper care for the facts is to become a fundamentalist.

You only have to take two comments from public figures to see the raft of disgusting generalisations and speculations that guide this brand of thought. Alan Dershowitz, professor of Law at Harvard, aired a commonly held, oft unchallenged view of Hamas’ tactics in conversation with Piers Morgan. According to Dershowitz, the Israeli bombing of the Al-Dalou family home in which four children died on 18th November was a deliberate ploy by Hamas to gain sympathy from the international media: “Hamas was firing rockets in order to induce [Israel] to kill the family… It’s called the dead baby strategy… They want their children to be martyred so they can carry them out… and thereby gain an advantage over Israel.” He presents not an ounce of evidence – and the notion eerily echoes the blood libels about which Jews have been tormented since the Middle Ages.

And such prejudices seem to be shared by those in government. Danny Ayalon, Israel’s current Deputy Foreign Minister (though he won’t stand at the next Knesset), betrayed his misunderstanding of the nuances of the situation in an interview with ‘The Takeaway’. “I would say that most of the people that were hit in Gaza deserved it,” he claimed, “as they were just armed terrorists”. Try telling that to the grieving parents.

This is not to say that Hamas is blameless. Doubtless similar (if not identical) beliefs exist in the Palestinian community. Both sides have their terrorists, their extremists, their fundamentalists – and some of those killed may well have been legitimate targets, even if they were attacked in illegitimate ways that caused disproportionate and inappropriate damage. But it can do no harm to see things from both perspectives: the fact is that Israel is the occupier, and its actions are in nobody’s interests. The destruction they cause hurts Gazans before backfiring on Israel with the radicalisation of more and more Palestinians. Indeed, truisms have a knack of remaining true – there’s no smoke without fire. As American historian Juan Cole put it when talking about his own country’s foreign policy, “When you bomb people and kill their family, it pisses them off. They form lifelong grudges… This is not rocket science. If they were not sympathetic to the Taliban and al-Qa’ida before, after you bomb the shit out of them, they will be.”

What’s needed is a drastic shift in attitude. The re-humanisation of the Palestinians could not come quickly enough. Unflinching support of a destructive policy, both from within and without Israel, which succeeds in demeaning, demonising and degrading the enemy will keep peace forever at arm’s length. What’s worse is that it will allow the fundamentalists on both sides to thrive, dividing two peoples whose similarities (as it has been acknowledged so many times) are far greater than their differences.

For me and many others, the image that defined this brief battle in a seemingly interminable war was that of the four Al-Dalou siblings. Their corpses, limp and squashed together on the metal mortuary table, are marbled with bloody scars and debris. It’s an image of everything this conflict has become: amoral, inhuman, tragic. It’s an image that forces us to confront the feelings we must deaden in order to justify any fatal attack, whether Israeli or Palestinian: that ‘they’ are ultimately just as vulnerable as ‘us,’ just as mortal, just as human.