“They went up like men! They came down like animals!”

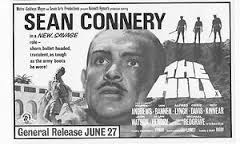

So ran the tagline to this 1965 drama set in a British military disciplinary camp located in the Libyan desert during World War Two. Why should you see it? Because not only is it one of Sean Connery’s finest performances, possibly even the finest, a performance void of the glamour, fanciful action and droll dialogue that his (up to then) three Bond movies had entertained us with and helped make him the global star that he was but it’s also packed with terrific performances from all the main players, it has splendid black and white cinematography and a script that crackles with grit and reality, racism and black humour in equal measure. Ray Rigby’s screenplay is brought to life by the masterful Sidney Lumet who once again manages to capture the claustrophobia of this confined space much as he did for those 12 Angry Men.

Whether or not you admire the acting talents of Sean Connery or Sir Sean as we now address him, you can’t help but admit the masculine presence he brought to the screen and his darkly brooding machismo was never more felt than in this film. He practically simmers with an aggression that is barely contained throughout and the honesty with which he portrays his disgraced soldier makes it at an absolute must see for anyone who appreciates star quality.

Connery plays Joe Roberts, a former squadron sergeant major sent to a military detention camp in the Libyan desert for assaulting his commanding officer. The camp is run with an iron rod-like efficiency by R.S.M Wilson (played by the eminently watchable Harry Andrews) who sees his role as correcting failed soldiers by breaking them down and then building them back up “into men!” as a vital part of the war. Alongside Wilson are staff sergeants Harris and Williams, two authority figures who could not be more different. Harris, played by Ian Bannen is a temperate officer and a decent man who has a measured amount of compassion for the prisoners in the camp as does the camp’s rather ineffectual Medical Officer (Michael Redgrave) but staff sergeant Williams (brilliantly portrayed by Ian Hendry) is an absolute rotter – a brutal and sadistic man who seems to find self worth in his prisoner’s suffering as well as seeing it as a means of impressing his superiors.

When Roberts arrives with four others at the camp, they are immediately given a taste of Williams’ harsh treatment by being ordered to climb up and down a man-made hill of sand and rock under the burning Libyan sun whilst carrying their full packs on their backs. For them, every day is filled with drills and exercise and all the while this punishment is dished out all too frequently and with far too much relish by Wilson and Williams. But when one of his fellow newcomers dies from this excessive punishment Roberts stands in defiance against the harsh running of the camp and in particular the viscous abuse dispensed by Staff Sergeant Williams.

What ensues is not only an explosive power struggle among the ranking officers of the camp but also a battle between the prisoners themselves as they struggle to contain their own pent up rage against the oppressive authority and the disrespect and dislike they harbour for each other. How hard a dilemma to decide whether to follow orders as you know you must or to risk court-martial or even firing squad to do what is right and humane?

Gripping stuff!